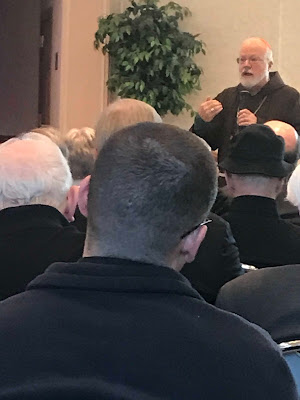

I am with the priests of the Archdiocese of Boston this afternoon as they hear reports about the Archdiocesan Pastoral Plan Disciples in Mission.

What wonderful priests go to make up this presbyterate, including our hard working alumni.

A fascinating and very informative discussion among men who love the Lord and his Church!

29 November 2017

28 November 2017

When you blunder...

A very wise man passed on this quote from Saint Louis de Montfort the other day. I was going to save it for a homily, but I just can't resist sharing it. A great consolation to us all!

“If you make a blunder

“If you make a blunder

which brings a cross upon you,

whether it be inadvertently

or even through your own fault,

bow down under the mighty hand of God

without delay,

and as far as possible do not worry over it…

"If there is anything wrong in what you have done,

accept the humiliation as a punishment for it;

if it was not sinful,

accept it as means of humbling your pride.

"Frequently, even very frequently,

God allows his greatest servants,

those far advanced in holiness,

to fall into the most humiliating faults

so as to humble them in their own eyes

and in the eyes of others.

"He thus keeps them from thoughts of pride

in which they might indulge

because of the graces they have received,

or the good they are doing,

so that ‘no one can boast in God’s presence.’”

Friends of the Cross, no. 46

27 November 2017

She Gave of Her Suffering - A Monday morning homily

Three sets of people today: Daniel and the men of Judah, the wealthy people and the poor widow. Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah sound a lot like you: “young men without any defect, handsome, intelligent and wise, quick to learn, and prudent in judgment.”

Come to think of it, the wealthy people sound like us too. They’re wealthy. Lots of gifts, just like the men of Judah.

And then there is the poor widow. Notice she is defined but what she has lost: no more husband and no more wealth. Poor widow.

That’s who they are. Now look at what they did. We’re told the men of Judah did the right thing, becoming vegetarians rather than breaking the kosher laws.

And the wealthy people did the right thing, too. They put their offering in the treasury. Doesn’t say how much. It could have been a little. It could have been a lot. But they put their offering in the treasury and probably went away satisfied with themselves.

But only the poor widow was worthy of the Lord’s praise, for, we are told, she “gave from her poverty.” The vegetables were probably tasty (after all, we’re told that Daniel and the gang looked better than everyone else after two weeks of a vegan diet) and the wealthy people felt pretty good about putting their envelopes in at Church.

But after giving away those two coins, the poor widow probably had to go to bed with a gnawing hunger, or do without that winter shawl or leave the broken window in the kitchen. The young men gave God their fidelity and the wealthy gave their money, but none were any the worse for wear. But she gave her suffering.

So maybe that’s the reason the Lord pointed her out. Because she gave the most precious gift: her suffering.

26 November 2017

Month's Mind Mass at Saint Paul's Cathedral

This morning I was privileged to celebrate a month's mind Mass at Saint Paul's Cathedral in Worcester, remembering my mother Marguerite Moroney and Julia Monroe, the mother of the Cathedral Director of Music, Richard Monroe, who died a week after my mother. Here's the text of my homily.

As another year of grace ends, the Church, appropriately enough, recalls what the Lord told us about the end of time.

And I have always been delighted by the practice followed by artists in the late middle ages of painting today’s Gospel on the back wall of almost every Church. So, as the people left Church, they would be reminded of the Last Things.

As another year of grace ends, the Church, appropriately enough, recalls what the Lord told us about the end of time.

And I have always been delighted by the practice followed by artists in the late middle ages of painting today’s Gospel on the back wall of almost every Church. So, as the people left Church, they would be reminded of the Last Things.

There, on one side of the door, the dead would rise from their graves, caught up in the air to be judged by Christ, reigning gloriously from a nimbus of light held aloft by angelic hosts.

Above the rising Saints, the angels gather the sheep who have kept his commandment to love others as he has loved them. They are the ones who have washed their robes in his blood and are now called to the Supper of the Lamb!

While on the other side were those who have not loved, those who had chosen the way of neglect and perdition and are now faced with what the Book of Revelation calls the "second death" (cf. Revelation 20:14-15; 21:8).

The wondrously perverse medieval mind depicted their tortures as commensurate with their sins; and while it is salutary to our souls to keep such gross reminders ever-before our wandering eyes, we must admit that no fire nor pincer nor other diabolic torture could ever approach the horror of being apart from the love of God…in utter aloneness, cold darkness and fear. Or, in the awful words of Pope Benedict: “…he who dies in mortal sin, without repentance, locked in prideful rejection of God's love, excludes himself from the Kingdom of life.”

Which is what brings us to the reason Jesus and the Church tell us this story today. It is not just to scare us, though scare us it should, but to inspire us to be good and to pray for those who have died.

Perhaps it is on purpose that the Church ends the month of November the same way she began, with prayers for the dead. For death does not end our relationships.

I often tell the seminarians that if someone gets up and preaches a long eulogy at my Funeral, they should throw something at them. For those who love me when I die will not praise me, but pray that my sins be forgiven.

When I die, my relationships will continue. Indeed, the commandment to love and honor my mother and my father and my grandparents continues to bind me to those who die. And as clearly as it bound me as a good son to go visit them in the nursing home and the hospital, it binds me still to pray for them.

I strated November on a rainy all Souls Day, by going to a florist not far from Saint John’s Cemetery in Worcester and purchasing twenty-four white roses. Over the next couple hours I then visited all of my relatives in Saint John’s Cemetery, putting a flower on each grave, singing the In paradisum and praying for them.

And in my calendar, I inscribe the dies natales, the day of birth unto eternal life, of each of my parents, grandparents and godparents, so that I can offer Mass for them on those days. Why? So that God will forgive whatever sins they may have committed and lead them home to himself. Or, as we prayed at my mother’s funeral:

O God, who alone are able to give life after death, free your servant Marguerite Mary from all sins, that she, who believed in the Resurrection of your Christ, may, when the day of resurrection comes, be united with you in glory.

Free your servant from her sins! Kyrie eleison! That is the prayer and the work we owe to the dead. For, as Saint Augustine once preached:

"…there is no doubt that the dead are helped by the prayers of the Holy Church, by the saving sacrifice, and by alms dispensed for their souls; these things are done that they may be more mercifully dealt with by the Lord than their sins deserve."

So let us end the month of November as we began it, by praying of the dead, begging God to forgive their sins. And while we are at it, let us ask God to forgive us our sins and lead us to everlasting life.

22 November 2017

On Death...November Rector's Conference

Here is the text of my November Rector's Conference, a meditation on death delivered on All Soul's Day.

Two nights ago was Halloween, the night on which, each year, I become famous. At 10:00pm, as on every Halloween, the History Channel replayed an old documentary entitled Exorcism: Driving Out the Devil. I served as what they call the “base interview” for that documentary, so once a year people hear my (now twenty year older) voice wax eloquent on things that go bump in the night!

Now, mine is, admittedly, a rather ignominious fame, I must admit, for it feeds off a fascination with the supernatural and with death, drawn from and, for the History Channel at least, best incarnated in Halloween

For Halloween is the opening of what since the fifteenth century has been referred to as Allhallowtide, the triduum of All Hallows Eve, All Hallow’s Day, and All Souls Day.

In Mexico these days are commemorated with the public holiday of Día de Muertos, as families erect ofrendas altars in their homes in commmeoration of and intercession for their beloved dead.

But even in secular cultures and networks throughout the world, these are, truly, the days of the dead…replete with Halloween marathons of deadly horrors. They play all the scariest horror movies, from The Shining to Freddy on Elm Street.

Why do we get such a thrill from being terrified by such horror genres? I turn to Stephen King in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre, who writes: “We take refuge in make-believe terrors so the real ones don’t overwhelm us, freezing us in place and making it impossible for us to function in our day-to-day lives. We go into the darkness of a movie theater hoping to dream badly, because the world of our normal lives looks ever so much better when the bad dream ends.

“And then the end of the movie comes. The last “saucer has been shot down by Hugh Marlowe’s secret weapon, an ultrasonic gun that interrupts the electromagnetic drive of the flying saucers, or some sort of similar agreeable foolishness. Loudspeakers blare from every Washington street corner, seemingly: “The present danger . . . is over. The present danger . . . is over. The present danger is over…[And] for a moment—just for a moment—the paradoxical trick has worked. We have taken horror in hand and used it to destroy itself….

Think of the frightened little kids, screaming their way through a Frankenstein movie, who emerging from the theatre have conquered the monster and the witch who hides in the closet and even the bully who awaits them next recess. They have looked into the face of horror and emerged into the clear sunlight of invincibility.

So Halloween is all about demons and devils and death….about all that goes bump in the night…But most of all it’s about our fear of death’s unwillingness to negotiate with us, its inevitability and its threat of the cold black darkness which awaits.

Which is why All Hallows Eve makes such a great prelude to the proclamation of the Gospel! For along with all the fear and superstition and mythology of boogey-men in the night is the popular cultural prejudice, deeply held even among un-believers, that Catholics do death better than almost anyone else.

I’m reminded of the comment of a not overly-devout Jacqueline Kennedy, widow of the slain president, who faced the terrible prospect of attending the Funeral of her assassinated brother-in-law, Robert Kennedy, in 1968. As she ascended the steps of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral with the mourners, Arthur Schlesinger took her arm and she declared in a stage whisper: “These Catholics really know how to do death.”

A more recent story. Father Busch recently told me about how he was recently called to the hospital in the middle of the night because someone was dying. He entered the room, introduced himself, and quickly found out that neither the dying person nor any other member of the family was Catholic. So, he gently inquired why they called for a Catholic Priest. “Well,” the wife replied, “whenever someone is dying in the movies they call for a priest, so we figured that’s what you’re supposed to do.”

So what does the American culture believe about death? A quick insight might come from two movie clips, both from the 1983 movie Terms of Endearment, which includes two great death scenes, the first with Deborah Winger and the second with the inimitable Shirley MacLaine.

In the first scene with Deborah Winger, her children tearfully bid her goodbye. I dare you to watch that scene on youtube without crying. But what does it tell us that death is all about? About saying goodbye and loving the people you love until your last breath. It’a about looking back, because there’s not much in front of you but fond memories.

And then there’s the scene in which the curmudgeonly character played by Shirley MacLaine dies. It is both humorous and touching, and it ends with her recalling the joy of her life, softly saying: “I was in a place. I had a daughter. And I was loved.”

Her words tell us that the common way of facing death is to speak in the past tense. It’s about remembering, in the words of Simon of Garfunkel:

“Time it was, and what a time it was, it was

A time of innocence, a time of confidences

Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph

Preserve your memories, they're all that's left you.”

The American way of death is, therefore, caught up in the notion of “memorialization,” remembering yesterday, until the memories fade. Remembering.

Now remembering is not bad. In fact, it is healthy. I spent several hours the day after my mother’s death putting together that video of just such times to play in the background at my mother’s wake. Remembering is good.

But for Catholics (we who do death so well) it’s not just or even primarily about looking back, but looking ahead. Having stood by the deathbed of hundreds of folks for almost forty years as a priest, and having just buried my mother two weeks ago, it’s a question pretty close to my heart: What’s death about?

And the Church has received from her Lord three simple answers which the world always has and probably always will find hard to understand.

1. Death is about leaving

2. Death is about arriving

3. Death does not end relationship….

First, Death is about leaving...now and at the hour of our death....The hour of our death. What is it like and what is it all about? In other words, what is death going to be like?

From the first centuries of her life the Church has seen death as a Transitus or passage from this world to Christ. Thus the Liturgy of Christian dying is set in front of a door with the saints of the Church militant gathered around you on this side. And the heavenly hosts ready to greet you on the other.

Listen to the prayers for the Commendation of the Dying and te prayers for immediately after death.

"I commend you, my dear sister, to almighty God, and entrust you to your Creator. May you return to him who formed you from the dust of the earth. May holy Mary, the angels, and all the saints come to meet you as you go forth from this life. May Christ who was crucified for you bring you freedom and peace. May Christ who died for you admit you into his garden of paradise. May Christ, the true Shepherd, acknowledge you as one of his flock. May you see the Redeemer face to face, and enjoy the vision of God for ever.

'Go forth, Christian soul, from this world in the name of God the almighty Father, who created you, in the name of Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who suffered for you, in the name of the Holy Spirit, who was poured out upon you, go forth, faithful Christian. May you live in peace this day, may your home be with God, with Mary, the virgin Mother of God, with Joseph, and all the angels and saints."

Indeed, we embraced this idea of death as Transitus when we buried my mother two weeks ago to the strains of two ancient hymns: the Sancti Dei. And the In paradisum. This Transitus, this passing through a door from this life to the next, is best understood when seen as a participation in the Paschal suffering, death and resurrection of the same Christ to whom we are journeying. For our death is a participation in his Paschal dying. Our suffering is joined to his blessed passion as with Christ we commend our spirit to God and with our final breath offer all that we are and have been as an offering to him. I remember years ago witnessing the death of a good priest who experienced his death as nothing less than the final and definitive participation of the offering of your sacrifice and mine to God the Father Almighty.

While the Christian sees the moment of death as an imitation of the perfect sacrifice offered by his Lord upon the cross, a final kenotic self-offering, a trustful falling into the arms of God, the culture in which we live has an often conflicting vision characterized by the struggle for control to the end!

We see this so starkly in the attitudes of those who would seek only to celebrate what has gone before and are paralyzed in the face of death. Just as the fear of death and of dying has driven the “assisted suicide” movement. As Pope francis reminds us:

“If death is seen as the end of everything, death frightens us, it terrifies us, it becomes a threat that shatters every dream, every promise, it severs every relationship and interrupts every journey. This happens when we consider our lives as a span of time between two poles: birth and death; when we fail to believe in a horizon that extends beyond that of the present life; when we live as though God did not exist.

“Jesus’ invitation to be ever ready, watchful, knowing that life in this world is given to us also in order to prepare us for the afterlife, for life with the heavenly Father. And for this there is a sure path: preparing oneself well for death, staying close to Jesus.”

So death is about leaving, but is is also about arriving; and there is a strange tension which runs through the prayers of Roman Catholic Funeral Liturgy which is analogous to the the already, but not yet of Roman Catholic Eschatology.

Here, by way of example, are two prayers from the Order of Christian Funerals:

"O God, in whose presence the dead are alive

and in whom your Saints rejoice full of happiness,

grant our supplication, that your servant John,

for whom the fleeting light of this world shines no more, may enjoy the comfort of your light for all eternity. "

Free your servant John, we pray, O Lord,

from every bond of sin, that he, who in this world

was found worthy to be conformed to Christ,

may be raised to the glory of the resurrection

and draw the breath of new life among your Saints. "

OK, so which is it? Does it mean that the dead person has arrived at the beatific vision or that he is in a holding room, a place of purification or has he been immediately consigned to the everlasting fires of hell?

Well, yes. It means both. For, admittedly, there are some precisions about about life after death which are obscured by the fact that it takes place beyond the constraints of time and space and and is not fully known by we who still perceive through a glass darkly. So, with that admitted incapacity, let me place before you three thoughts of what’s on the other side of that door.

First, our patron was quite clear about the other side of the door: “Beloved, we are God’s children now; but what we shall later be has not yet come to light.” (1 John 3:2) Much as we will never know the day nor the hour, we will never know the details of what God has in store for us.

Second, for the just, there is the assurance that on the other side of the door we call death, the angels wait to lead us into the paradise, the martyrs stand ready to welcome us and all the saints prepare to lead us home to the heavenly Jerusalem, where there is no need of sun or moon, for the light of God’s glory illumines every soul.

For, in the words of our beloved Pope emeritus: “those who commit themselves to live like him are freed from the fear of death, no longer showing the sarcastic smile of an enemy but offering the friendly face of a "sister," as St. Francis wrote in the "Canticle of Creatures." In this way, God can also be blessed for it: "Praise be to you, my Lord, for our Sister Bodily Death." We must not fear the death of the body, faith reminds us, as it is a dream from which we will awake one day.

And third thing we know about death, is that it will lead to our judgement.

I have always admired the medieval tradition of painting the Last Judgement on the back wall of every Church, above the door which people must use to return to their daily lives. There, invariably, the dead rise from their graves and are caught up in the air to be judged by Christ, reigning gloriously from a nimbus of light held aloft by angelic hosts.

On his right, the Lord gathers the sheep, who have kept his commandment to love others as he has loved them. They are the ones who have washed their robes in the blood of the Lamb and are now called to the Supper of the Lamb!

But on his left, are those who have not loved, those who have chosen the way of perdition and now face what the Book of Revelation calls the "second death" (cf. 20:14-15; 21:8).

The wondrously perverse medieval mind depicts their tortures as commensurate with their sin. And while it is salutary to our souls to keep such gross reminders ever before our wandering eyes, one must admit that no fire nor pincer nor other diabolic torture could ever approach the horror of being apart from the love of God…in utter aloneness, cold darkness and fear. Or, in the awful words of Pope Benedict:

“…he who dies in mortal sin, without repentance, locked in prideful rejection of God's love, excludes himself from the Kingdom of life.”

Which is what brings us to the third thing which the Church teaches about death:

That Death does not end our relationships. If someone gets up and preaches a long eulogy at my Funeral, please throw something at them.

Now, mine is, admittedly, a rather ignominious fame, I must admit, for it feeds off a fascination with the supernatural and with death, drawn from and, for the History Channel at least, best incarnated in Halloween

For Halloween is the opening of what since the fifteenth century has been referred to as Allhallowtide, the triduum of All Hallows Eve, All Hallow’s Day, and All Souls Day.

In Mexico these days are commemorated with the public holiday of Día de Muertos, as families erect ofrendas altars in their homes in commmeoration of and intercession for their beloved dead.

But even in secular cultures and networks throughout the world, these are, truly, the days of the dead…replete with Halloween marathons of deadly horrors. They play all the scariest horror movies, from The Shining to Freddy on Elm Street.

Why do we get such a thrill from being terrified by such horror genres? I turn to Stephen King in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre, who writes: “We take refuge in make-believe terrors so the real ones don’t overwhelm us, freezing us in place and making it impossible for us to function in our day-to-day lives. We go into the darkness of a movie theater hoping to dream badly, because the world of our normal lives looks ever so much better when the bad dream ends.

“And then the end of the movie comes. The last “saucer has been shot down by Hugh Marlowe’s secret weapon, an ultrasonic gun that interrupts the electromagnetic drive of the flying saucers, or some sort of similar agreeable foolishness. Loudspeakers blare from every Washington street corner, seemingly: “The present danger . . . is over. The present danger . . . is over. The present danger is over…[And] for a moment—just for a moment—the paradoxical trick has worked. We have taken horror in hand and used it to destroy itself….

Think of the frightened little kids, screaming their way through a Frankenstein movie, who emerging from the theatre have conquered the monster and the witch who hides in the closet and even the bully who awaits them next recess. They have looked into the face of horror and emerged into the clear sunlight of invincibility.

So Halloween is all about demons and devils and death….about all that goes bump in the night…But most of all it’s about our fear of death’s unwillingness to negotiate with us, its inevitability and its threat of the cold black darkness which awaits.

Which is why All Hallows Eve makes such a great prelude to the proclamation of the Gospel! For along with all the fear and superstition and mythology of boogey-men in the night is the popular cultural prejudice, deeply held even among un-believers, that Catholics do death better than almost anyone else.

I’m reminded of the comment of a not overly-devout Jacqueline Kennedy, widow of the slain president, who faced the terrible prospect of attending the Funeral of her assassinated brother-in-law, Robert Kennedy, in 1968. As she ascended the steps of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral with the mourners, Arthur Schlesinger took her arm and she declared in a stage whisper: “These Catholics really know how to do death.”

A more recent story. Father Busch recently told me about how he was recently called to the hospital in the middle of the night because someone was dying. He entered the room, introduced himself, and quickly found out that neither the dying person nor any other member of the family was Catholic. So, he gently inquired why they called for a Catholic Priest. “Well,” the wife replied, “whenever someone is dying in the movies they call for a priest, so we figured that’s what you’re supposed to do.”

So what does the American culture believe about death? A quick insight might come from two movie clips, both from the 1983 movie Terms of Endearment, which includes two great death scenes, the first with Deborah Winger and the second with the inimitable Shirley MacLaine.

In the first scene with Deborah Winger, her children tearfully bid her goodbye. I dare you to watch that scene on youtube without crying. But what does it tell us that death is all about? About saying goodbye and loving the people you love until your last breath. It’a about looking back, because there’s not much in front of you but fond memories.

And then there’s the scene in which the curmudgeonly character played by Shirley MacLaine dies. It is both humorous and touching, and it ends with her recalling the joy of her life, softly saying: “I was in a place. I had a daughter. And I was loved.”

Her words tell us that the common way of facing death is to speak in the past tense. It’s about remembering, in the words of Simon of Garfunkel:

“Time it was, and what a time it was, it was

A time of innocence, a time of confidences

Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph

Preserve your memories, they're all that's left you.”

The American way of death is, therefore, caught up in the notion of “memorialization,” remembering yesterday, until the memories fade. Remembering.

Now remembering is not bad. In fact, it is healthy. I spent several hours the day after my mother’s death putting together that video of just such times to play in the background at my mother’s wake. Remembering is good.

But for Catholics (we who do death so well) it’s not just or even primarily about looking back, but looking ahead. Having stood by the deathbed of hundreds of folks for almost forty years as a priest, and having just buried my mother two weeks ago, it’s a question pretty close to my heart: What’s death about?

And the Church has received from her Lord three simple answers which the world always has and probably always will find hard to understand.

1. Death is about leaving

2. Death is about arriving

3. Death does not end relationship….

First, Death is about leaving...now and at the hour of our death....The hour of our death. What is it like and what is it all about? In other words, what is death going to be like?

From the first centuries of her life the Church has seen death as a Transitus or passage from this world to Christ. Thus the Liturgy of Christian dying is set in front of a door with the saints of the Church militant gathered around you on this side. And the heavenly hosts ready to greet you on the other.

Listen to the prayers for the Commendation of the Dying and te prayers for immediately after death.

"I commend you, my dear sister, to almighty God, and entrust you to your Creator. May you return to him who formed you from the dust of the earth. May holy Mary, the angels, and all the saints come to meet you as you go forth from this life. May Christ who was crucified for you bring you freedom and peace. May Christ who died for you admit you into his garden of paradise. May Christ, the true Shepherd, acknowledge you as one of his flock. May you see the Redeemer face to face, and enjoy the vision of God for ever.

'Go forth, Christian soul, from this world in the name of God the almighty Father, who created you, in the name of Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who suffered for you, in the name of the Holy Spirit, who was poured out upon you, go forth, faithful Christian. May you live in peace this day, may your home be with God, with Mary, the virgin Mother of God, with Joseph, and all the angels and saints."

Indeed, we embraced this idea of death as Transitus when we buried my mother two weeks ago to the strains of two ancient hymns: the Sancti Dei. And the In paradisum. This Transitus, this passing through a door from this life to the next, is best understood when seen as a participation in the Paschal suffering, death and resurrection of the same Christ to whom we are journeying. For our death is a participation in his Paschal dying. Our suffering is joined to his blessed passion as with Christ we commend our spirit to God and with our final breath offer all that we are and have been as an offering to him. I remember years ago witnessing the death of a good priest who experienced his death as nothing less than the final and definitive participation of the offering of your sacrifice and mine to God the Father Almighty.

While the Christian sees the moment of death as an imitation of the perfect sacrifice offered by his Lord upon the cross, a final kenotic self-offering, a trustful falling into the arms of God, the culture in which we live has an often conflicting vision characterized by the struggle for control to the end!

We see this so starkly in the attitudes of those who would seek only to celebrate what has gone before and are paralyzed in the face of death. Just as the fear of death and of dying has driven the “assisted suicide” movement. As Pope francis reminds us:

“If death is seen as the end of everything, death frightens us, it terrifies us, it becomes a threat that shatters every dream, every promise, it severs every relationship and interrupts every journey. This happens when we consider our lives as a span of time between two poles: birth and death; when we fail to believe in a horizon that extends beyond that of the present life; when we live as though God did not exist.

“Jesus’ invitation to be ever ready, watchful, knowing that life in this world is given to us also in order to prepare us for the afterlife, for life with the heavenly Father. And for this there is a sure path: preparing oneself well for death, staying close to Jesus.”

So death is about leaving, but is is also about arriving; and there is a strange tension which runs through the prayers of Roman Catholic Funeral Liturgy which is analogous to the the already, but not yet of Roman Catholic Eschatology.

Here, by way of example, are two prayers from the Order of Christian Funerals:

"O God, in whose presence the dead are alive

and in whom your Saints rejoice full of happiness,

grant our supplication, that your servant John,

for whom the fleeting light of this world shines no more, may enjoy the comfort of your light for all eternity. "

Free your servant John, we pray, O Lord,

from every bond of sin, that he, who in this world

was found worthy to be conformed to Christ,

may be raised to the glory of the resurrection

and draw the breath of new life among your Saints. "

OK, so which is it? Does it mean that the dead person has arrived at the beatific vision or that he is in a holding room, a place of purification or has he been immediately consigned to the everlasting fires of hell?

Well, yes. It means both. For, admittedly, there are some precisions about about life after death which are obscured by the fact that it takes place beyond the constraints of time and space and and is not fully known by we who still perceive through a glass darkly. So, with that admitted incapacity, let me place before you three thoughts of what’s on the other side of that door.

First, our patron was quite clear about the other side of the door: “Beloved, we are God’s children now; but what we shall later be has not yet come to light.” (1 John 3:2) Much as we will never know the day nor the hour, we will never know the details of what God has in store for us.

Second, for the just, there is the assurance that on the other side of the door we call death, the angels wait to lead us into the paradise, the martyrs stand ready to welcome us and all the saints prepare to lead us home to the heavenly Jerusalem, where there is no need of sun or moon, for the light of God’s glory illumines every soul.

For, in the words of our beloved Pope emeritus: “those who commit themselves to live like him are freed from the fear of death, no longer showing the sarcastic smile of an enemy but offering the friendly face of a "sister," as St. Francis wrote in the "Canticle of Creatures." In this way, God can also be blessed for it: "Praise be to you, my Lord, for our Sister Bodily Death." We must not fear the death of the body, faith reminds us, as it is a dream from which we will awake one day.

And third thing we know about death, is that it will lead to our judgement.

I have always admired the medieval tradition of painting the Last Judgement on the back wall of every Church, above the door which people must use to return to their daily lives. There, invariably, the dead rise from their graves and are caught up in the air to be judged by Christ, reigning gloriously from a nimbus of light held aloft by angelic hosts.

On his right, the Lord gathers the sheep, who have kept his commandment to love others as he has loved them. They are the ones who have washed their robes in the blood of the Lamb and are now called to the Supper of the Lamb!

But on his left, are those who have not loved, those who have chosen the way of perdition and now face what the Book of Revelation calls the "second death" (cf. 20:14-15; 21:8).

The wondrously perverse medieval mind depicts their tortures as commensurate with their sin. And while it is salutary to our souls to keep such gross reminders ever before our wandering eyes, one must admit that no fire nor pincer nor other diabolic torture could ever approach the horror of being apart from the love of God…in utter aloneness, cold darkness and fear. Or, in the awful words of Pope Benedict:

“…he who dies in mortal sin, without repentance, locked in prideful rejection of God's love, excludes himself from the Kingdom of life.”

Which is what brings us to the third thing which the Church teaches about death:

That Death does not end our relationships. If someone gets up and preaches a long eulogy at my Funeral, please throw something at them.

When I die, our relationship will continue. Indeed, the commandment to love and honor my mother and my father and my grandparents continues to bind me to those who die. And as clearly as it bound me as a good son to go visit them in the nursing home and the hospital, it binds me still to pray for them.

For years now, on Memorial Day and all Souls Day, I go to a florist not far from Saint John’s Cemetery in Worcester and purchase twenty-four white roses. Over the next couple hours I then visit all of my relatives in Saint John’s Cemetery, put a flower on their grave, sing the In paradisum and pray for them.

This morning it was a terrible beauty to pray at the grave of my mom and dad just as I prayed for them at the Altar this morning, and will once again on November 19th, April 19th and October 19th next year, offering the Holy and Living Sacrifice a month, six months and a year from her death.

In fact, in my calendar, I inscribe the dies natales, the day of birth unto eternal life, of each of my parents, grandparents and godparents, so that I can offer Mass for them on those days. Why? So that God will forgive whatever sins they may have committed and lead them home to himself. Or, as we prayed at my mother’s funeral:

O God, who alone are able to give life after death, free your servant Marguerite Mary from all sins, that she, who believed in the Resurrection of your Christ, may, when the day of resurrection comes, be united with you in glory.

Free your servant from her sins! Kyrie eleison! That is the prayer and the work we owe to the dead. For, as Saint Augustine once preached:

"…there is no doubt that the dead are helped by the prayers of the Holy Church, by the saving sacrifice, and by alms dispensed for their souls; these things are done that they may be more mercifully dealt with by the Lord than their sins deserve. The whole Church observes the custom handed down by our fathers: that those who died within the fellowship of Christ’s body and blood should be prayed for when they are commemorated in their own place at the holy sacrifice, and that we should be reminded that this sacrifice is offered for them as well.… people whose love for their dead is spiritual as well as physical should pay much greater, more careful and more earnest attention to those things – sacrifices, prayers, and almsgiving – which can assist those who though their bodies may be dead, to be alive in the spirit."

That’s why we pray in the Roman Canon: Remember also, Lord, your servants James and Marguerite, who have gone before us with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace. Grant them, O Lord, we pray, and all who sleep in Christ, a place of refreshment, light and peace

But this is not what most of the world believes. They seek not a Funeral Mass, a holy and living sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins, but a “Celebration of Life” in which Memorializes, looks back and rejoices in what has been, with little mention of what will be.

Contrast that reality with the profoundly Catholic moment when we learned by the tolling of a bell that beloved Pope John Paul II has died. Thousands of people, in Piazza san Pietro and around the world stopped, bowed their heads and prayed, as the bell tolled through electronic devices throughout the world. It was a moment of hope and of promise, as our beloved Pope returned to the Father’s house.

Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord.

And let perpetual light shine upon them.

May they rest in peace. Amen.

May their souls and the souls of all he faithful departed, through the mercy of God rest in peace. Amen.

For years now, on Memorial Day and all Souls Day, I go to a florist not far from Saint John’s Cemetery in Worcester and purchase twenty-four white roses. Over the next couple hours I then visit all of my relatives in Saint John’s Cemetery, put a flower on their grave, sing the In paradisum and pray for them.

This morning it was a terrible beauty to pray at the grave of my mom and dad just as I prayed for them at the Altar this morning, and will once again on November 19th, April 19th and October 19th next year, offering the Holy and Living Sacrifice a month, six months and a year from her death.

In fact, in my calendar, I inscribe the dies natales, the day of birth unto eternal life, of each of my parents, grandparents and godparents, so that I can offer Mass for them on those days. Why? So that God will forgive whatever sins they may have committed and lead them home to himself. Or, as we prayed at my mother’s funeral:

O God, who alone are able to give life after death, free your servant Marguerite Mary from all sins, that she, who believed in the Resurrection of your Christ, may, when the day of resurrection comes, be united with you in glory.

Free your servant from her sins! Kyrie eleison! That is the prayer and the work we owe to the dead. For, as Saint Augustine once preached:

"…there is no doubt that the dead are helped by the prayers of the Holy Church, by the saving sacrifice, and by alms dispensed for their souls; these things are done that they may be more mercifully dealt with by the Lord than their sins deserve. The whole Church observes the custom handed down by our fathers: that those who died within the fellowship of Christ’s body and blood should be prayed for when they are commemorated in their own place at the holy sacrifice, and that we should be reminded that this sacrifice is offered for them as well.… people whose love for their dead is spiritual as well as physical should pay much greater, more careful and more earnest attention to those things – sacrifices, prayers, and almsgiving – which can assist those who though their bodies may be dead, to be alive in the spirit."

That’s why we pray in the Roman Canon: Remember also, Lord, your servants James and Marguerite, who have gone before us with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace. Grant them, O Lord, we pray, and all who sleep in Christ, a place of refreshment, light and peace

But this is not what most of the world believes. They seek not a Funeral Mass, a holy and living sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins, but a “Celebration of Life” in which Memorializes, looks back and rejoices in what has been, with little mention of what will be.

Contrast that reality with the profoundly Catholic moment when we learned by the tolling of a bell that beloved Pope John Paul II has died. Thousands of people, in Piazza san Pietro and around the world stopped, bowed their heads and prayed, as the bell tolled through electronic devices throughout the world. It was a moment of hope and of promise, as our beloved Pope returned to the Father’s house.

Eternal rest grant unto them O Lord.

And let perpetual light shine upon them.

May they rest in peace. Amen.

May their souls and the souls of all he faithful departed, through the mercy of God rest in peace. Amen.

20 November 2017

Leaving the Shadow of the Dome...

As the sun rises over Saint Peters, I head to the airport after a quick and deeply satisfying trip to meet with the wonderful officials of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas in Rome. As you may have heard, Saint John’s Seminary is now proudly affiliated with this venerable institution which traces its earliest roots to the studium established by Saint Dominic in 1222 AD

Last night, Father Cessario joined me for dinner with the new Rector of the Angelicum, Father Michał Paluch O.P. On behalf of Cardinal O’Malley and Saint John’s Seminary I thanked him for the wonderful opportunity of affiliation with the university and we discussed many possibilities for collaboration in the years to come. Earlier in the day, Father Cessario and I met with the Dean, Father Stipe Juric, OP and Sister Catherine J.Droste, OP, Vice Dean of the Angelicum.

Over the weekend I also saw our old friend Father Ward, who joined us for dinner with a table full of SJS alumni. A quick, but deeply rewarding trip…now back to Boston to give thanks!

16 November 2017

Boston Ministers' Club at SJS

I was honored this evening to host a meeting of the Boston Ministers’ Club, a monthly gathering of the pastors and ministers of many of Boston’s most venerable congregations. This evening I was honored to present a paper on the topic: “A Few Ecumenical Perspectives on the Translation of Liturgical Texts.” Here is a copy of my text.

Forty eight years ago I was in seventh grade, just about five years after the Second Vatican Council had approved the idea of translating the Latin Prayers of the Roman Catholic Mass from Latin to English.

The first guidelines for this new endeavor were published in January under the title Comme le prevoit. Later that year, the now six year old International Commission on English in the Liturgy undertook an ecumenical outreach in the hope that some of the translations might be developed in concert with those churches which also used these same ancient texts in their worship.

ICET

Thus was born the International Consultation on English Texts, which over the next six years produced common texts for use in each of their denominations under the title Prayers We Have in Common. Those prayers consisted of the

In 1975 the translations of the Creeds was incorporated into the new Roman Missal proposed by the International Commission on English in the Liturgy, approved by the Roman Catholic Conferences of English-speaking Bishops and confirmed by the Holy See.

ELLC

ICET was succeeded by the English Language Liturgical Consultation (ELLC) in 1985, the American section of which was comprised of the Consultation on Common Texts. The new organization, formed here in Boston during a meeting of Societas Liturgica was given “a more clearly defined membership and even broader goals for ecumenical-liturgical collaboration.” National or regional representatives were drawn from the Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, Reformed (Presbyterian), Roman Catholic, and United/Uniting traditions, while at a later date Orthodox and other Eastern Churches, as well as representatives of the Free Churches began to take part in CCT meetings.

In 1990 ELLC produced an updated and expanded edition of common texts under the title Praying Together. This revised collection of texts included

By the late-1990s many of the prayer texts had been adopted by the various denominational bodies involved in their composition. However, an ELLC survey published in 2001 reported widespread modification of almost all of the texts by most denominations. Let’s look at three of the most popular texts by way of example: The Gloria in Excelsis, the Nicene Creed and the Sanctus and Benedictus.

Gloria in Excelsis

The ELLC survey reported widespread dissatisfaction with particular words in the translation, although it had been widely adopted. But most notably there was difficulty with the systematic avoidance of masculine pronouns referring to God.

Here was an important indication of a growing disagreement among the churches in regard to masculine prenominal references to God.

Some maintained that the predominantly masculine references to God in the scriptures (at least numerically predominant) should be taken as a mandate (so to speak) for masculine images of God in our prayer texts.

On the other hand, many saw masculine prenominal references as growing from a sinfully patriarchal view of God and authority which it was the responsibility of those seeking justice to dismantle.

More intense expressions of the conservative point of view saw in the inclusivists a tendency to strip personhood from the heart of trinitarian Doctrine and an attempt to censor or at very least critique the scriptural writers with an evolving gender-inclusive ideology.

More intensive expressions of the more liberal point of view resulted in formulations for Baptismal formulae invoking God as ““Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier,” as well as the avoidance of the use of masculine prenominal references as universal collectives.

This brief sketch of the emerging debates of inclusive language in liturgical texts is not designed to adequately describe the subject, so much as to mark one of the significant sources of contention which still exist among the Churches in the translation of liturgical texts.

Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed, as one might expect, has been modified by various denominations along doctrinal lines. The Evangelicals in the Church of England, for example, modified references to Mary, while multiple denominations approached the translation of consubstantial in creative ways, an irony if there ever was one since the very word consubstantialis and homoousious before it were “invented words” for a fairly indescribable concept. As the ELLC survey concluded:

“It is beyond the scope of this report to suggest any resolution. For the time being we should accept that the difficulty will be dealt with by “local” amendments…The importance of the Nicene Creed is seen in the weight of comment its attracts. However, it alone led respondents to offer complete texts as alternative models.”

Sanctus and Benedictus

And finally, the Sanctus and Benedictus. Here, too, there were major points of diversion from the ELLC text, some revolving around the Christological nuance of “Blessed is he.”

Some saw this as a rather explicit Christological referent, while other, preferring “Blessed is the one,” thus providing the major source of variation. Those who defend “Blessed is he” see a direct Christological reference. Those who advocate “Blessed is the one” expressed “a referred Christology in which the congregation who come are the Body of Christ, ‘neither male nor female“. The Australian Lutheran Church preferred a stronger translation of Sabaoth, etc. etc.

SO WHERE TO FROM HERE?

The fabric of the attempt to reach a solid ecumenical corpus of prayers in common had, therefore, begun to fray by the turn of the millennium along the lines of doctrinal, linguistic and translation lines. All of which presaged the siesmic shifts experienced by Roman Catholics in the move from dynamic to formal equivalence promulgated by the publication of the instruction Liturgiam authenticam in 2001.

So where does that leave us today in seeking common renderings of those ancient prayers which have the potential to remind us of our common roots, giving voice to a common lex orandi which would lead to a common lex credendi? For the weaving of such an introcate tapestry of belief and praise is our heart’s desire and an answer to the Lord’s own prayer of ut unum sint.

It leaves us, I would suggest, with several major challenges which it may well take another generation to unravel. But as long as we’re setting out challenges, let me add one more.

Rhetorical Style. It is one of the most puzzling of all the questions of translation faced by any denomination and has been the major point of conflict in the Roman Church’s struggles in rendering liturgical texts over the past twenty years, an enterprise to which I have given much of my professional life.

As a Church and as a society we are, as the linguists would say, shifting registers. All you need do is listen to the ways in which the genre of presidential addresses have changed in the past fifty years. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson sound entirely different from Presidents George W Busch and Trump.

For an extreme but illuminating example, take President Lincoln’s second inaugural address, in which he sought to use poetry to knit together a broken country:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Compare that, if you will, to this excerpt from our most recent President’s inaugural address.

I will fight for you with every breath in my body. And I will never, ever let you down. America will start winning again, winning like never before. We will bring back our jobs. We will bring back our borders. We will bring back our wealth, and we will bring back our dreams. We will build new roads and highways and bridges and airports and tunnels and railways all across our wonderful nation. We will get our people off of welfare and back to work rebuilding our country with American hands and American labor. We will follow two simple rules -- buy American and hire American.

Substance aside, the change in rhetorical tone bears similarities to the shift in tone from middle to modern English. The first is resonant with chiasmatic structure, soaring poetic visions and calls to arms. The second is characterized by the staccato rhythms of a teletype and the pithy headlines of the Tabloid.

And I present these examples not to stand in the long line of those who would beat up on our President, for he is what we, as a country, have chosen. Banished from the courtroom, the classroom and the political rostrum is the high rhetoric of even a few decades ago.

In my communion, as you probably know, attempts in recent years to translate the texts of the ancient sacrmanetaries precisely have included a return to high rhetorical style, much to chagrin of fans of more contemporary forms of expression.

Let’s take a look at a a Christmas Collect, found in many of your service books, by way of example.

The Latin original dates from the 9th century Gelasian Sacrmanetaries and has always been used for Masses during the night before Christmas:

Deus, qui hanc sacratissimam noctem

veri luminis fecisti illustratione clarescere,

da, quaesumus, ut, cuius in terra mysteria lucis agnovimus,

eius quoque gaudiis perfruamur in caelo.

Here’s the new precise translation, written like its Latin original, in pretty High Rhetorical style:

O God, who have made this most sacred night

radiant with the splendor of the true light,

grant, we pray,

radiant with the splendor of the true light,

grant, we pray,

that we, who have known the mysteries of his light on earth,

may also delight in his gladness in heaven.

It’s not dissimilar to the rendering in the1979 Book of Common Prayer:

O God,

who hast caused this holy night to shine

with the illumination of the true Light:

Grant us, we beseech thee,

that as we have known the mystery of that Light upon earth,

so may we also perfectly enjoy him in heaven;

Compare the rhetorical style of those prayers to the 1970 ICEL:

Father

You make this holy night

radiant with the splendor of Jesus Christ our light.

We welcome Him as Lord, true light of the world.

Bring us to eternal joy in the kingdom of heaven

where he lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit

one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

or the 1985 Book of Alternative Services:

Eternal God,

this holy night is radiant

with the brilliance of your one true light.

As we have known the revelation of that light on earth,

bring us to see the splendor of your heavenly glory;

through Jesus Christ our Lord, who is alive and reigns

with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever.

Or still more, these lines from the second form of the Christmas Litany in the Presbyterian Book of Common Worship:

God of grace and truth,

In Jesus Christ you came among us

As light shining in darkness.

We confess that we have not welcomed the light,

Or trusted good news to be good….

Forgive our doubt, and renew our hope,

So that we may receive the fullness of your grace,

and live in the truth of Christ the Lord.

Lots of good prayers, but written in two essentially different registers: maybe described as high Church and low Church, transcendent and imminent or uppity and low brow. But that tone, I would suggest, the choice of thick poetry or crisp prose, is one of the most important challenges before us.

For beyond the words, our denominational worship and identity is formed as much by the way we say the words as what those words are, by the way we approach the Godhead as what we say to him when we get there.

And maybe there’s a message in there somewhere: that, as the philosopher Rudolph Otto once reminded us: before the numinous all words ultimately fail and all we can really do is bow down very low.

Thank you.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

The troubled relationship of Saul and David continues today. As each pursue the other. But then a remarkable thing happens, as David has Sa...